Now Yahweh said to Abram, “Leave your country, and your relatives, and your father’s house, and go to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation. I will bless you and make your name great. You will be a blessing.I will bless those who bless you, and I will curse him who treats you with contempt. All the families of the earth will be blessed through you.” Genesis 12:1-3

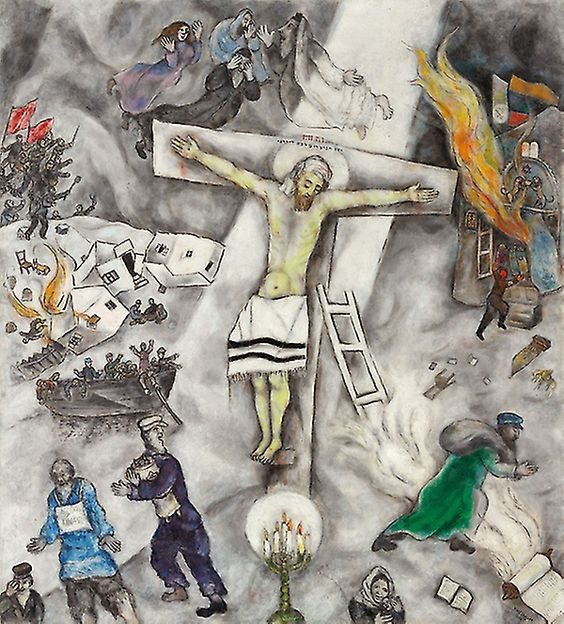

At first glance, this seems like a conventional albeit Modernist crucifixion painting. But do a double take and you’ll see the images surrounding Christ are not related to the Biblical event of the crucifixion at all.

In this painting, Marc Chagall connects the persecution and death of Christ to the persecution and death of huge numbers of other Jews happening at the time in Russia during the pograms and in Eastern Europe by the Nazis, culminating in Kristallnacht, that horrifying “night of broken glass.” Scattered throughout the gray, billowing background there are soldiers raiding a village and a synagogue and setting them on fire with looted, destroyed items, including Torah scrolls, strewn about. Jews are escaping by boat and on foot. One man desperately clutches a Torah as he flees with only one shoe on. Another man carries his only earthly belongings in a sack and prays as he runs. Toward the bottom, a mother comforts her baby.

The crucifixion scene itself, bathed in a flattened spotlight, is also changed to explicitly reflect the “Jewishness” of Christ. His loincloth is a prayer shawl, the crown of thorns is swapped for a headcloth, a menorah stands at His feet, and instead of mourning angels flying above Him, Old Testament figures bitterly weep. The artist here is saying that the Nazis and other Anti-Semitic persecutors are just the same as those who killed Christ. This is interesting, and ingeniously cutting since the crucifixion of Christ has historically been used as an excuse for Anti-Semitism. Some Nazis actually professed to be Christians. But here, he draws attention to the fact that these atrocities are being committed against God’s own people, the people from whom Christ came. In God’s unique design, without the Jewish people, there would be no salvation for humanity at all. Chagall is celebrated as both the quintessential modern artist and the greatest Jewish artist of the 20th century. The style he developed actually combines all of the major styles of early Modernism: Fauvism, Symbolism, Cubism, and Surrealism. But at the same time, his work is also completely and uniquely Jewish. Many Jewish artists used Modernism to hide their culture and religion, but he used Modernism to memorialize it. He grew up in a working-class Hassidic Jewish community in Vitebsk, then part of the Russian Empire. That heritage became the source of imagery for his work, which is often a disorienting array of figures, animals, and domestic and religious objects portrayed in soft brushstrokes, vivid colors, and an intriguingly collapsed sense of space. The state of his personal faith is unclear, as he did not really practice any religion, but as he grew older, he became increasingly more inspired by the Bible and painted many illustrations of Bible stories. He also increasingly sought to draw connections between the Jewish religion and Christianity, and the Jewish experience to the human experience. He rightly saw his very specific community as a symbol for all of humanity itself. After all, they are God’s chosen people, whom He used to save the world. God promised Abraham from the very beginning that the whole world would be blessed through him. Jesus was the fulfillment of that promise, and He will one day set up His kingdom on the earth, just as prophesied by all the Old Testament prophets who bore witness to wave after wave of persecution and held on to that destiny as their hope.